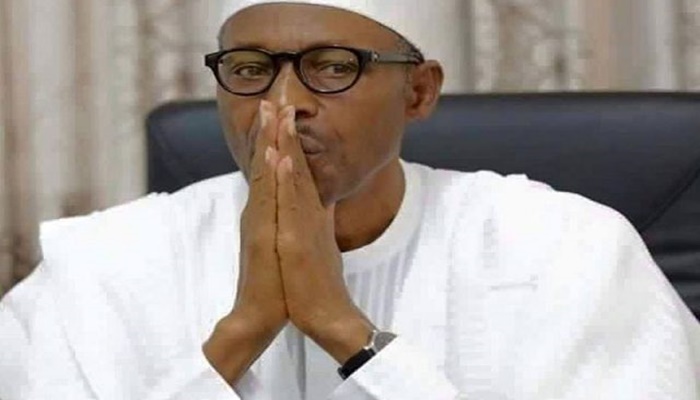

Ahead Feb 16 presidential poll, BBC puts President Buhari on the scale

As Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari seeks re-election, he must do without the decisive factor behind his victory four years ago – the promise of a clean break from the past.

Back then, he represented a new broom, the symbol of his party. He had never been democratically elected despite having tried three times, and his public image – as a dour, incorruptible disciplinarian – was based on a 20-month stint as military leader, back in the 1980s.

He campaigned as a born-again democrat, vowing to root out corruption, revive the economy and defeat the Islamist Boko Haram insurgency. An electorate worried about corruption, insecurity and the economy took him at his word, making him the first Nigerian opposition candidate to defeat an incumbent president.

Mr Buhari’s victory in 2015 was not just an endorsement of his platform but also an indictment of the politics that preceded him. This election, in turn, will pass judgement on the politics of his term. He can no longer promise a clean break from a past of which he is a part.

His record in office is mixed. Mr Buhari’s critics say that the very attributes that won over voters four years ago – his strictness and inflexibility – have emerged as liabilities. They accuse him of autocratic leanings as well as a disastrous tendency towards inaction. He took six months to appoint his cabinet, and has earned himself the nickname, “Baba-Go-Slow”.

Mr Buhari’s supporters can argue that he has largely delivered on campaign pledges such as tackling corruption and cracking down on Boko Haram. But they may struggle to point to concrete achievements in other fields, such as fixing the economy.

The economy slid into recession while he was in office, dragged under by a sharp fall in the global price of oil. The downturn was exacerbated by Mr Buhari’s opposition to devaluing the naira, which led to a severe foreign currency shortage in the first year of his term.

Companies that had to import goods and equipment were forced to rely on a black market in US dollars which had emerged to circumvent the fixed currency rate. Unemployment also doubled – a particularly troubling statistic in a country where two-thirds of the population live below the poverty line.

As a result, many Nigerians will look back on Mr Buhari’s first presidential term as a time when their money worries intensified and their living standards took a hit. His prospects for re-election will be influenced by the extent to which they hold him personally responsible for their hardships.

On the positive side, the president boosted investment in agriculture and infrastructure projects, and oversaw a rise in oil production in the south. He can also take some credit for eventually bringing the economy out of recession, although the recent rise in the global price of oil played the bigger part in this, and the recovery has been sluggish.

Mr Buhari’s tenure has also been marked by intense speculation about his health. Since 2017, the president has often been away from Nigeria, receiving medical treatment. While the 76-year-old has refused to disclose the nature of his ailment, he was forced to deny that he had hired a body double to replace him at public events.

His power base lies with the poor of northern Nigeria, known as the “talakawa” in the Hausa language. In the last election, his nationwide appeal was boosted by the backing of prominent defectors from the then governing People’s Democratic Party (PDP). This time round, his key asset is believed to be his running mate, Yemi Osinbajo, a popular pastor from the largely Christian south of the country.

Among his successes, Mr Buhari can point to an improvement in security in the north-east. Under his watch, the Nigerian military has retaken territory from Boko Haram militants that had been fighting to overthrow the government and create an Islamic state.

Scores of schoolgirls that were part of a group of nearly 300 abducted by the militants have also been reunited with their families. However, many of the so-called Chibok girls remain missing, and recent attacks by a Boko Haram faction have underscored the fragility of the security gains.

According to Andrew Walker, a Nigeria analyst who has written a book about Boko Haram, the insurgent group has a record of using lulls in the fighting to regroup. “Mr Buhari was able to ride a period of low activity from Boko Haram, which now appears to be coming to an end,” he says.

Personal integrity

Nigeria’s security worries are not limited to the north-east. The impoverished north-western state of Zamfara has seen a sharp rise in kidnappings and killings linked to gangs of cattle rustlers, bandits and vigilantes.

Violence has also flared in other parts of the country with a history of ethnic and religious conflicts. Troops had to be deployed in central regions after deadly clashes between farmers and Fulani cattle-herders. Meanwhile, the long-dormant Biafran separatist movement in the south-east has been rekindled.

After four years of the Buhari presidency, Mr Walker says: “More and more Nigerians are asking whether personal integrity alone is enough to maintain the integrity of the country”.

Mr Buhari’s personal reputation for incorruptibility has indeed survived his time in office – a rare feat among Nigerian leaders. However, he has been accused of using corruption investigations as a blunt instrument to neutralise his political opponents.

In January 2019, Mr Buhari suspended Nigeria’s chief justice, Walter Onnoghen, over his alleged failure to declare his personal assets before taking office in 2017. The timing of the move, weeks before the general election, provoked alarm.

As the country’s top law official, Judge Onnoghen would have played a vital role in overseeing potential electoral disputes. However, Mr Buhari dismissed concerns – voiced by foreign observers and opposition politicians – that the suspension had anything to do with the elections.

Dissatisfaction with Mr Buhari’s leadership has also rippled through the ranks of his party, the All Progressives Congress (APC). In 2018, the APC was weakened by a series of high-profile defections, with dozens of legislators crossing the floor to join the PDP.

An early indication that all was not well came in 2016, when the first lady, Aisha Buhari, told the BBC’s Hausa service that a small clique had hijacked her husband’s administration, assuming responsibility for presidential appointments.

The attack from close quarters was unusual and particularly damning for a leader who had promised to crack down on nepotism.

Mr Buhari responded to the criticism by saying that his wife “belongs in the kitchen”, which did his international reputation no favours.

Whip-wielding soldiers

Mr Buhari was born in 1942, to a large Muslim family in the northern Katsina state. In a 2012 interview, he described a childhood memory of being thrown from the back of the horse with his father and half-brother.

After finishing his schooling, he entered a military academy, joining the Nigerian army soon after the country gained independence from the UK. He received his officer training in the UK. Years later, he would attribute his love of discipline to his schooling and to his military background, crediting these institutions with having taught him the virtue of hard work.

He rose through the ranks of the military while it tightened its grip on post-independence Nigeria through a series of coups. As a colonel, he won admiration for driving back an incursion by Chadian soldiers who had occupied islands in Lake Chad that belonged to Nigeria.

By the end of the 1970s, he had served as a governor of the north-east, and as a de facto oil minister under Olusegun Obasanjo, the military ruler who would return to power decades later as an elected president, a trajectory that Mr Buhari would eventually follow.

In 1983, he became head of state after a coup against the elected government of Shehu Shagari. Mr Buhari would later downplay his role, insisting that the real power lay with the coup plotters behind the scenes, but this account has been disputed.

His regime is remembered for its campaign against indiscipline and corruption, as well as for its human rights abuses. Hundreds of people – including politicians, businessmen and journalists – were jailed under repressive laws. The regime also locked up the Nigerian musical legend and perennial government critic, Fela Kuti, on trumped-up charges relating to currency exports.

On the streets, Nigerians were ordered to queue while waiting for buses, watched over by whip-wielding soldiers, while civil servants who were late for work were publicly humiliated by being forced to perform frog jumps.

The regime’s curb on imports led to job losses and business closures, and a new currency was introduced in an effort to tackle corruption. Prices rose, living standards fell, and after 20 months, Mr Buhari was forced out by another coup, engineered by the army chief, Gen Ibrahim Babangida.

Despite his professed conversion to democracy years later, Mr Buhari has always defended the 1983 coup, arguing that the military only stepped in when “the elected people had failed the country”.

Mr Buhari has been married twice, first to Safinatu Yusuf, and then to Aisha Halilu. He has 10 children.